January 09, 2020

Globalization has created a more competitive business environment without regard for borders. Companies feel pressured to expand to new markets or redefine existing ones. The corresponding demand for employees has been great, challenging organizations to change how they think about meeting workforce needs. Overall, there is an increased recognition that employees are a key business asset.

With an eye to the long-term sustainability of their organizations and the productivity and engagement of future and existing employees, global employers are increasingly concerned about the health of their workers around the world. Although many U.S. companies have long provided health benefits and resources globally, they have not always done so strategically and with clear objectives. “There is (now) a global movement among multinationals to respond to the need for a healthier workforce ... (by) integrating wellness (and holistic well-being) into their companies’ culture.”1

Wellness and well-being have different meanings around the world and may not always translate easily. As companies develop a strategy and objectives for promoting and impacting employee health, the goal should always be to promote the improved physical, social, emotional and financial health and well-being of populations (i.e., the workforce) through education and/or intervention. Increasingly, there is a desire to offer benefits and create programming that effectively addresses the individual needs of employees and their relationships to the business and the community.

Companies continue to strive to have a healthier workforce.2 What follows is a business case for developing a corporate approach to well-being globally. Much of the argument is based on existing theories, hypotheses and research. As the research on corporate programs and initiatives outside the U.S. builds in coming years, so too will the scholarly support of wellness and well-being programs globally.

The Importance of Corporate Wellness Initiatives

Over the past three decades, corporate wellness and wellbeing programs offered by U.S. multinationals and focusing on U.S. employees have become the norm. These workplace-centered health interventions have had an impact at every level, including with individuals, the workforce and the broader population. Initiatives are designed to address modifiable employee health behaviors (e.g., smoking, obesity and physical inactivity) in familiar, convenient and trusted environments. The objectives are to achieve a positive impact on health outcomes and reduce health care costs.

Companies rarely seek healthy employees for the sake of healthy employees. The focus on health and the support of healthy employees are rooted in promoting other business drivers: economic outcomes, productivity, safety, employee engagement, loyalty, reputation, sustainability and corporate social responsibility. These established connections constitute the true foundation for corporate action on employee health.

Wellness and well-being initiatives may take a variety of forms, varying in intention, comprehensiveness, intensity and duration.5 Functionally they run the gamut from one-off interventions targeting singular health care concerns (e.g., tobacco cessation benefits, on-site flu vaccination, etc.) to multifaceted programs designed to impact total health, such as broad-based health education and awareness initiatives, health risk appraisals, targeted educational materials and customized counseling.6

“Health is not only of great value to individuals and populations, but also to business and industry. Enlightened employers – whether small, medium, or large – are beginning to see benefits … of good health as an investment to be leveraged.”7

Logic and research support the value of addressing individual health in the workplace. “The workplace is organically connected to the home and to physical communities in which workplaces exist. Health behaviors extend across all three environments and cannot be artificially separated.” That environment can be a classroom for teaching healthy behavior that extends to the home as well as to the wider community.7

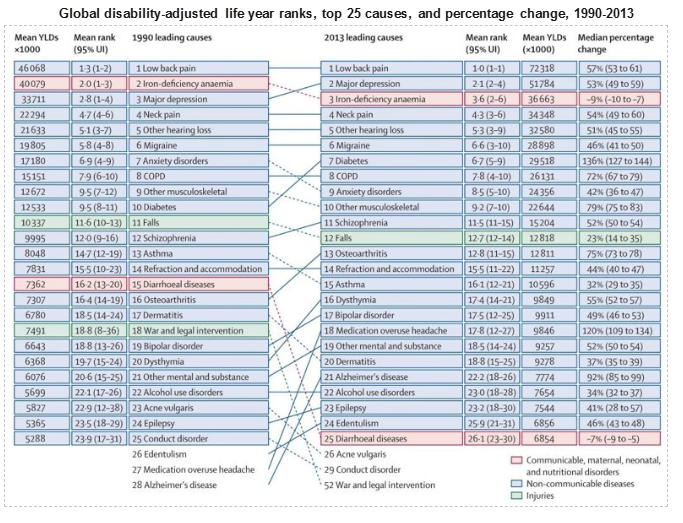

The workplace is a logical venue to address health issues because of how well it aligns the needs of all relevant stakeholders, including individuals, families, employer and community. Research has shown that wellness or health promotion programs can effectively improve employee health long-term.6 “Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) kill 40 million people each year.”8 “Four major NCDs – cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes– account for over 82% NCD deaths around the world.”8 The majority – up to 80% - of premature deaths from these diseases could be prevented by tackling just three risk factors: poor diet (including harmful use of alcohol), tobacco use and lack of physical activity.”9 These same factors are associated with five of the top 20 most costly physical health conditions for U.S. employers: chest pain, diabetes, heart attack, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and back pain.8 Top causes of global disability, a major corporate cost driver, include low back pain, major depressive disorders, neck pain, other musculoskeletal problems and migraine.11 All of these many challenges can be and have long been effectively addressed at the workplace.

The financial repercussions of unhealthy employees on organizations are well-documented and varied, including both direct costs (e.g., health care claims) and indirect costs (decreased productivity given increased absenteeism, presenteeism and workplace accidents).12 Corporate health interventions can lower employee health risks and overall organizational spend. “Employees with modifiable health risks have higher medical care and productivity expenses when compared with lower-risk employees.” With each identified risk, the associated costs increase incrementally.13

Employers want to see a return on investment (ROI) from employee health, wellness and well-being programs. Companies “are hoping to get something out of it. And that something is [the health] of this employee, who’s not just more productive, but uses less health care.”14 By improving organizational and individual health status, well-being programs are expected to produce a healthier workforce which, in turn, strengthens the company’s competitive edge in the marketplace.

The Business Case for Wellness: Data from the U.S. and Beyond

Most of the literature to date on the effectiveness of corporate wellness initiatives was conducted in the United States. For that reason, estimates of the return on an employer’s investment in wellness take into account U.S. centric costs and benefits, including employee medical costs and estimates of productivity losses and gains. As such, the direct applicability of that U.S. research on ROI* to a global setting is questionable. However, it is important to remember that a company reaps many positive, if less tangible, benefits from providing wellness programs that are no less economically valuable than direct medical spend. These include decreased employee absenteeism and increased productivity, greater talent attraction, increased employee retention and higher company morale. These benefits, which are not always easily quantified, are truly universal and coalesce to produce a stronger organization.

*Companies driven to promote wellness outside the United States by a desire for a return on their investment from doing so need to reset their expectations. In the United States those calculations include the benefit companies experience given a change in medical claims/health plan usage. Outside the U.S., employers do not necessarily incur the costs of employee and dependent health. That fundamentally changes the equation for wellness’ ROI.

Entire companies accrue value from investing in wellness. “Health promotion interventions delivered at the worksite can be efficiently and cost-effectively provided, especially when company leadership, norms, culture and policies are aligned to support adoption of healthy habits and prevention practices.”5 Consider existing research findings to date from the U.S. and around the world; according to:

- One study, wellness programs (of which fitness is a component) can return as much as six times their cost to the companies that sponsor them.15

- A 2012 analysis of 62 studies, “summary evidence continues to be strong with average reduction in sick leave, health plan costs, and workers’ compensation and disability insurance costs of around 25%.16

- A 2010 meta-analysis, for every dollar spent on workplace disease prevention and wellness programs, medical and absenteeism costs drop by $3.27 and $2.73, respectively.17

- A 2008 review of 55 UK workplace health studies found identified business benefits including less sickness absence, less staff turnover, less accidents/ injuries, greater employee satisfaction, less resource allocation, improved company profile, greater productivity, improved health & welfare, decreased claims and increased competitiveness & profitability.18

- A 2005 review of the evidence from 56 global peer reviewed studies found the benefits of workplace-health initiatives included a 27% reduction in sick leave absenteeism 26% reduction in health-care costs; 32% reduction in workers’ compensation and disability management cost claims; and a nearly 6 to 1 ROI.19

One company’s investment in wellness and health promotion led to decreased rates of obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, tobacco use, physical inactivity and poor nutrition.20 Ultimately, every dollar spent on programming produced a return on investment of between $1.88 to $3.92 or $565 per employee (2009 dollars).18 Employee productivity has shown a direct association with the number of health risks. As health risks decline, employee productivity improves.21, 22 Additionally, “comprehensive well-structured wellness programs contribute to attracting and retaining employees.”23

A Rationale for Implementing Wellness Strategies Globally

The world is suffering increasingly from preventable illness. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)* are now responsible for 82% of global deaths annually.24 By 2030, NCD-related deaths will number 52 million.26 Not only common in wealthy countries, 87% of all NCD deaths occur in middle income and developing countries.8 In India, for example, chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, mental health disorders, diabetes and cancer) and injuries are the leading causes of both death and disability.24 Yet, “80% of heart disease, stroke and type-2 diabetes and approximately 40% of cancers can be prevented through cost-effective interventions which address the primary risk factors.28

Three poor health behaviors contribute to the world’s high rate of NCDs: unhealthy diet (including harmful alcohol use and excess salt/sodium intake), tobacco use and physical inactivity. The leading risk factors for mortality are raised blood pressure (responsible for 19% of all deaths globally), tobacco use, excess salt/sodium intake, excessive alcohol use (including cancer) and physical inactivity, physical inactivity.8

Developing economies face evolving health care challenges. These countries report increasing first world health concerns (e.g., cardiovascular disease) alongside third world infectious diseases (e.g., malaria). Experience shows that with economic growth comes greater use of tobacco, decreased physical activity, increased consumption of alcohol and an increase in unhealthy diets.

- Tobacco: Almost 6 million people die from direct tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure each year. By 2030, this number is expected to increase to 8 million and account for 10% of all global deaths.24

- Insufficient physical activity: Physical inactivity is associated with 3.2 million deaths each year around the world. Those who are insufficiently physically active have a 20% to 30% increased risk of all-cause mortality.30

- Raised blood pressure: About 9.4 million deaths and 7% of disease burden are caused by raised blood pressure.24

- Overweight and obesity: At least 2.8 million people die each year due to being overweight or obese.31

- Raised cholesterol: Approximately 2.6 million deaths annually are associated with raised cholesterol.8 Harmful use of alcohol: About 5.9% of all deaths in the world (3.3 million people) each year occur as the result of the harmful use of alcohol.32

Ultimately, as globalization and urbanization intensify, people’s health behaviors change (e.g., they are more sedentary, have poorer eating habits and experience more stress). This results in higher rates of NCD. Increased incidence of preventable disease has a long lasting toll on quality of life. Between 1990 and 2010, disability rates around the world have risen dramatically.

Preventable illness handicaps economic growth around the world. Estimates are that the global economic impact (cumulative output loss) of major NCDs between 2011 and 2030 will be $30 trillion.33

In 2010, China estimated $23.03 trillion on NCDs while India reported related costs of $4.58 trillion.35

These numbers were expected to further double or triple by 2015. A 10% increase in country-level NCD burden translates into a 0.5% reduction in annual economic growth.27 In China, without government action, the cost of cardiovascular diseases, stroke and diabetes alone was estimated to be over US $550 billion between 2005 and 2015.30 When factoring in the societal costs of poor health, reducing cardiovascular disease mortality by 1% per year would increase China’s GDP by 15% (U.S. $2.34 trillion).31

Disease patterns around the world are driven in part by demographic shifts; populations globally are aging. Since 1970, the average age of death has increased by 35 years.36

In the subsequent 30 years lifespan gains in:

- East Asia were 30 years.

- Tropical Latin America were 32 years.

- Middle East and North Africa were an average of 30 years.

- Eastern sub-Saharan Africa were 12 years.9 “In 2015, one in eight people worldwide were aged 60 or over. By 2030, older persons are projected to account for one in six people globally.”37 In certain geographies, extreme population aging poses significant societal and economic risk. In Japan, currently, 33% of citizens are aged 65 and older; by 2050, that number will grow to 40%.37 Additionally, the country’s death rate (9.6 deaths/1,000 population) has outstripped its birthrate (7.8 births/1,000 population).38 This is taking a toll on the country’s social support programs, its national healthcare system, and on all workplaces.39

Business Stake in Global Wellness

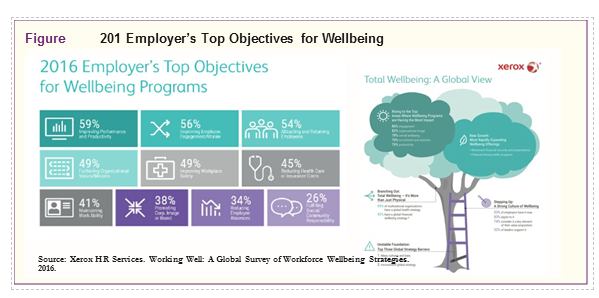

The demand for wellness programs and health promotion is growing around the world. Companies are looking for consistent, logical approaches to impacting health that are grounded in principles and outcomes. They want systems and solutions that are integrated with company’s strategy that is also global in direction.

Whereas wellness was once thought of as relevant only in the United States due to its ever-growing medical costs, it is now being considered in the context of global health awareness. Companies are seeing how poor population health has the potential to impact long-term business health. They are experiencing population health shifts firsthand. Workers around the world are increasingly affected by widespread lifestyle risks ranging from stress and mental disorders to obesity and heart disease.41 Creating a culture of well-being is an emerging objective for companies globally as well; 33% of respondents report a strong culture of wellbeing but 83% aspire to it in the future. The importance of a holistic approach to wellbeing, beyond the physical health, is an important tool for employers. About 74% of survey participants view their well-being program as an important element of their employee value proposition, aiding in recruitment and retention.42

Employers are looking to leverage wellness approaches globally to impact employees’ poor health trends. Threefourths of respondents say their wellbeing initiatives have produced a medium or high impact on improving employee engagement and morale, organization image, overall employee well-being, ability to attract employees and worker performance and productivity.42

Improving employee productivity is a rising strategic objective of employers globally. One reason for the drive is the the desire to establish the connection between well-being and productivity.

There is a progression toward offering more well-being programs. Increasingly, companies are including financial well-being in their overarching strategy (42%).42

Although companies have defined goals for their wellness programs around the world, most do not measure results. Data availability and analytics remains an area ripe for improvement. Only 36% surveyed companies have measured specific outcomes for their global wellness and well-being efforts.42

Challenges to Global Corporate Wellness

Large employer global wellness efforts are tested by a number of factors. Employers report that insufficiencies in the following areas are the top barriers to achieving their global health care objectives: differing cultures, laws, and practices as well as lack of global oversight for health or financial strategy.42 Employers know much less than they would like about the health of employees around the world. About one-third of organizations with operations in multiple countries have a global health and productivity strategy.43 However, about 28% do not have a global, regional or location-specific in place.43 Regardless of quality, this data affords limited specificity upon which to set country-level health objectives or to judge health change that is needed.

Companies must look to other sources of information for guidance about employee health status. When creating company health initiatives, they often rely on limited population health data or develop their own employee health data collection efforts. Companies that have implemented an employee health assessment (HA) globally cannot fully leverage or analyze that information. They are challenged to integrate HA data with medical and disability claims data, as is commonly done in the United States. However, the quality and utility of the data outside the U.S. is not the same. Ultimately, these data challenges complicate calculating ROI for wellness initiatives conducted outside the United States.

Employers have limited resources available globally to promote their global wellness and well-being ambitions. Health care markets in many locations have not yet evolved to provide the services, critical thinking or problem-solving that U.S. employers have come to expect. Although global employee assistance program (EAP) and health risk assessments (HRA) vendors do exist, there are few truly global wellness vendors. Thus, companies often must chart their course with inadequate and untested external support.

Employees globally may also have varying opinions about the role an employer should play in personal health. There are varying cultural attitudes about communicating openly about health – with family, peers and/or the extended community, such as in the workplace. Integral to this are different perspectives on personal privacy.

Companies at the forefront of providing health promotion or wellness globally have rooted those efforts in existing and long-standing corporate priorities and stressed the organization’s culture of safety or health care vocation. For example, a company that routinely collects data about employee risk exposure may:

- Leverage those same systems to better understand employee health risks and status; and

- Establish accountability for health by creating reporting systems throughout the organization.

As companies expand their wellness focus to the global arena, they should recognize the value of fully integrating all health-related efforts into corporate culture.6 Integration of corporate health pursuits is challenging. As documented by Hymel et al, even in the U.S., few employers are truly integrated. According to the 2016 Employee Health and Business Success survey, 56% of employers globally do not have a health and productivity strategy and instead simply offer various health and well-being programs.43 This “lack of integration prevents optimal resource utilization and impedes efforts to maximize the overall health and productivity of the workforce.” As wellness and wellbeing initiatives evolve globally, companies may be able to strategically avoid these pitfalls.7

Conclusion

What will make for a successful corporate wellness and/or well-being program globally? According to Mercer research, workplace wellness programs that are most successful are based on four elements: executive commitment and leadership; management support and participation; employee participation; and a committee of engaged employees.23

For global wellness and/or well-being programs to be truly effective, the issues addressed, the intervener, the education parlayed and/or the style of intervention must reflect local conditions and cultural preferences. Doing so necessitates understanding the local environment and the prevailing health problems, their determinants and their impact on productivity. It also demands a balancing of focus, ownership, stylistic approach, depth and breadth of programs with what is organizationally and culturally appropriate.

More Topics

Articles & Guides- 1 | Stram R. Globally, wellness programs lead to healthier employees. Benefits Magazine. 2011;48(3):22-25.

- 2 | Levin-Scherz J. Time to reconsider well-being programs. Willis Towers Watson Wire. 2017.

- 3 | Yen L, Edington MP, McDonald T, Hirschland D, Edington DW. Changes in health risks among participants in the United Auto Workers-General Motors LifeSteps health promotion program. American Journal of Health Promotion. 16(1):7-15. 2001.

- 4 | McGlynn EA, McDonald T, Champagne L, Bradley B, Walker W. The Business Case for a Corporate Wellness Program: A Case Study of General Motors and the United Auto Workers Union. The Commonwealth Fund; April 2003.

- 5 | Goetzel RZ, Pronk NP. Worksite Health Promotion: How Much Do We Really Know About What Works? American journal of preventive medicine. 38(2):S223-S225. 2010.

- 6 | Heaney C, Goetzel R. A review of health-related outcomes of multi-component worksite health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion. 11(4):290-307. 1998.

- 7 | Hymel PA, Loeppke RR, Baase CM, et al. Workplace Health Protection and Promotion: A New Pathway for a Healthier-and Safer-Workforce. J Occup Environ Med. 53(6):695-702. 2011.

- 8 | World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 2017.

- 9 | C3 Collaborating for Health. Review: Workplace health initiatives: evidence of effectiveness. December 2011.

- 10 | Soler RE, Leeks KD, Razi S, et al. A Systematic Review of Selected Interventions for Worksite Health Promotion: The Assessment of Health Risks with Feedback. American Journal of Preventive Medicine.38(2):S237-S262. 2010.

- 11 | Global Burden of Disease Study C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet (London, England). 386(9995):743-800. 2015.

- 12 | Mills PR, Kessler RC, Cooper J, Sullivan S. Impact of a health promotion program on employee health risks and work productivity. American Journal of Health Promotion..

- 13 | Henke RM, Carls GS, Short ME, et al. The Relationship Between Health Risks and Health and Productivity Costs Among Employees at Pepsi Bottling Group. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010;52(5):519-527.

- 14 | Bernstein L. Corporate fitness programs survive hard times. The Washington Post. July 4, 2011.

- 15 | Berry L, Mirabito AM, Baun WB. What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harvard Business Review. Available at: http://hbr.org/2010/12/whats-the-hard-return-on-employee-wellness-programs/ar/1. Accessed: July 11, 2011.

- 16 | Chapman L. Meta-evaluation of worksite health promotion economic return studies: 2012 update. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2012; March/April:TAHP1-TAHP10.

- 17 | Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings. Health Affairs.29(2):304-311.

- 18 | UK Healthzone. Why should small and medium enterprises (SMEs) bother with a health and wellbeing strategy? 2009.

- 19 | Chapman L. Meta-evaluation of worksite health promotion economic return studies: 2005 update. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;19(6):1-11.

- 20 | Henke RM, Goetzel RZ, McHugh J, Isaac F. Recent Experience In Health Promotion At Johnson & Johnson: Lower Health Spending, Strong Return On Investment. Health Affairs. 2011;30(3):490-499.

- 21 | Burton WN, Conti DJ, Chen CY, Schultz AB, Edington DW. The role of health risk factors and disease on worker productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(10):863-877.

- 22 | Burton WN, Chen CY, Conti DJ, Schultz AB, Pransky G, Edington DW. The association of health risks with on-the-job productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(8):769-777.

- 23 | Champagne D, Brown S. Webinar: Health & Productivity - Health and Wellness. June 8, 2011.

- 24 | World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Switzerland: World Health Organinzation; 2014.

- 25 | World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2011. Geneva, Switzerland.

- 26 | World Economic Forum. Charter for Healthy Living. January 2013.

- 27 | Patel V, Chatterji S, Chisholm D, et al. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. The Lancet. 377(9763):413-428.

- 28 | World Economic Forum. The Workplace Wellness Alliance - Making the Right Investment: Employee Health and the Power of Metrics.

- 29 | World Health Statistics 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011.

- 30 | World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases: 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: Available at: http:// www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf; 2011.

- 31 | World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2016; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed April 28, 2017.

- 32 | World Health Organization. Alcohol. 2015; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs349/en/. Accessed April 28, 2017.

- 33 | World Economic Forum and Harvard School of Public Health. The global economic burden of non-communicable diseases. 2011.

- 34 | Glassman A. Global chronic disease: It’s not all about the money for once. The Atlantic. 2011.

- 35 | Bloom DE, Cafiero-Fonseca ET, McGovern ME, et al. The macroeconomic impact of non-communicable diseases in China and India: Estimates, projections, and comparisons. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 2014;4:100-111.

- 36 | The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy. Seattle, WA. 2013.

- 37 | United Nations. World Population Ageing. United Nations; 2015.

- 38 | Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. Japan. 2017; https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-worldfactbook/geos/ja.html. Accessed April 28, 2017.

- 39 | The Japan syndrome. The Economist. November 18, 2010.

- 40 | Buck Consultants. Working Well: A global survey of health promotion and workplace wellness strategies. November 2012.

- 41 | Stram R. Globally, wellness programs lead to healthier employees. Benefits Magazine. 2011;48(3):22-25.

- 42 | HR Services SO. Employee Productivity is the Top Priority for Wellbeing Programs According to Xerox Services Survey. 2016.

- 43 | Willis Towers Watson. Employee Health and Business Success. 2016.

- 44 | Greenbaum E, Lykens C. Access and Availability of Benefits Data. Washington, DC: Business Group on Health. May 2011.